Let’s get this out of the way…

Costa Rica is not known for its food.

Compared to the complex flavors of Mexico or the rich cuisine of Peru, Costa Rica doesn’t have much to brag about.

But Costa Ricans do excel at one thing: simple, home-style cooking.

Comfort food. Real comfort food — not the ironic fusion comfort food beloved by urban foodies. The kind cooked by abuelas (“grandmas”) a la leña (“wood-fired”), because every Costa Rican grandma knows a la leña is better.

When prepared with love (preferably overlooking a beautiful beach or lush mountain valley) Costa Rican food is undeniably satisfying.

And if you visit the Caribbean coast, home to a large Afro-Caribbean population, you’ll discover a truly remarkable local cuisine.

Costa Rica’s Best Food

Sadly, many tourists never taste Costa Rica’s best food. Expecting nachos, tacos and burritos, sunburnt gringos encounter chorreadas, patacones and chifrijo. Bewildered, they order a hamburger, which is always the worst thing on the menu.

Thus the stereotype of bad Costa Rican food lives on.

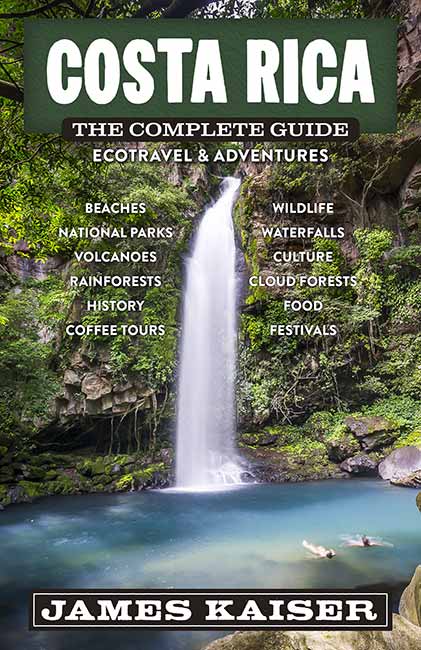

I adapted this page from my guidebook, Costa Rica: The Complete Guide. My goal is to expose travelers to the full spectrum of Costa Rican food.

Everyone learns about gallo pinto and casados. But seek out some of Costa Rica’s lesser-known specialties and you’ll eat cheaper, better and happier.

Table of Contents

1. Where to Find Authentic Costa Rican Food

2. The Classics

3. Soups & Stews

4. The Specialties

5. Caribbean Food

6. Desserts

See also:

Costa Rican Coffee

Fruit Drinks of Costa Rica

Costa Rican Beer, Rum & Liquor

Where to Find Authentic Costa Rican food

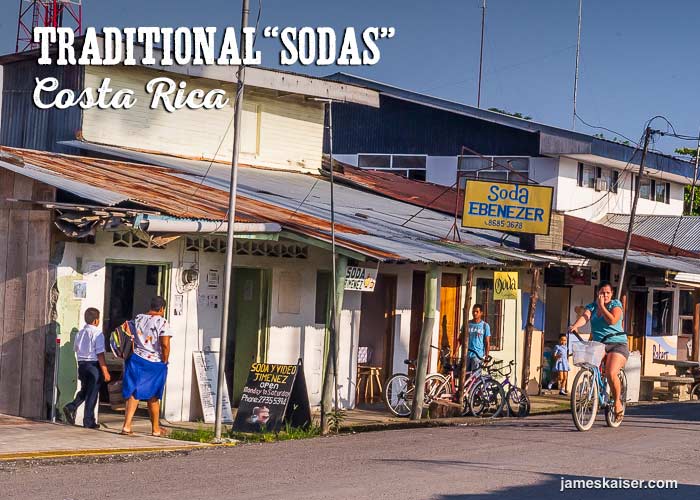

Outside of grandma’s house, you’ll find the best authentic Costa Rican food at sodas — a local word loosely translated as “diner.” Sodas are never fancy. In fact, many appear rundown, which is why many tourists avoid them.

Don’t make that mistake!

If you want to eat like a local, visit a soda. In my guidebook, Costa Rica: The Complete Guide, I list the best sodas in each town. I even include out-of-the-way, middle-of-nowhere sodas for adventurous gastronauts.

The Classics

Gallo Pinto

Any discussion of Costa Rican food starts with gallo pinto — the national dish of Costa Rica. No matter where you go in Costa Rica, they’ll serve gallo pinto for breakfast every single day.

Gallo pinto’s two main ingredients, rice and black beans, account for its name. Gallo pinto means “painted rooster” — a reference to the black and white speckling found on some roosters.

The beans and rice are spiced up with onions, celery, red peppers and cilantro. Gallo pinto is often served with eggs, tortillas, fried plantains, and natilla (sour cream). Salsa Lizano (a mass-produced Costa Rican condiment) is a popular add-on.

In my experience, gallo pinto almosts always tastes better in simple, cheap restaurants. Fancy restaurants and hotels tend to overprepare gallo pinto, which requires a rustic touch.

Costa Ricans (aka Ticos) are very proud of gallo pinto. There’s even a common expression: Mas Tico que gallo pinto (“More Tico than gallo pinto”).

Casado

The casado is Costa Rica’s second most famous dish. This lunch/dinner favorite is essentially a mixed platter of beef, chicken or fish with rice, beans, cabbage salad, tortillas and sweet fried plantains.

Casado literally means “married man.” It refers to the days when men working in the fields brought mixed lunches prepared by their wives, conveniently wrapped in a banana leaf.

Casados are generally the best value on any menu. And at restaurants where quality is questionable, casados are always your safest bet.

Patacones

Say hello to the most delicious snack you’ve never heard of.

These fried, mashed green plantains are popular throughout Central America and the Caribbean. But they aren’t nearly as popular in Mexico — so they are largely unknown in the United States. One exception is Miami, where Cubans call them “tostones.”

Patacones (pronounced “pah-tah-COE-nays“) go great with black bean dip or fresh guacamole.

Tamales

Tamales have been a staple of the Costa Rican diet since pre-Columbian times. They consist of masa (corn dough), meat, rice, and vegetables. This combo is then wrapped in a plantain leaf and steamed. As the mixture cooks, the leaf imparts a distinct earthy flavor to the dough.

Costa Ricans serve pork tamales as the main course for Christmas dinner. Costa Rican tamales tend to be softer and wetter than Mexican tamales, which are often wrapped in corn husks.

Costa Ricans call two tamales tied together in a package a piña (“pineapple”), though nobody seems to know why.

Chicharrón

Chicharrón is salty, greasy and delicious — three qualities gringos generally love. Why it’s not more popular in the U.S. is a mystery.

Chicharrón — pronounced “chee-char-RONE” — is basically just deep fried pork belly/pork rinds.

But don’t compare it to the packaged pork rinds for sale at 7-11. Or the overwrought $18 pork belly appetizers required by hipster law in gentrifying U.S. neighborhoods. Neither of those porquerías gives you any sense of the true delights of chicharrón.

Chicharrón is pure Costa Rican comfort food. Not trashy, not fancy. Served hot with a squeeze of lime, it’s divine.

Ceviche

Ceviche probably originated in Peru. Or maybe Ecuador. It’s definitely not from Costa Rica. But give Ticos credit for knowing a good thing when they taste it. Today you’ll find great ceviche appetizers in restaurants throughout the country.

Ceviche is chunks of raw fish marinated in citrus, often with thinly-sliced onions, red pepper and ciantro mixed in. The citric acid gently “cooks” the fish, yielding terrific flavor. (Scientifically speaking, the citrus denatures proteins in the fish.)

Costa Rican ceviche is often served with cheap, salted crackers. I’m generally opposed to such things, but when you’re eating fresh ceviche in front of the sparkling ocean in the tropics — hey, it works.

Costa Rican Soups

Olla de Carne

Literally “pot of beef,” olla de carne is Costa Rica’s most popular soup. Large and filling, it’s often served as a main course. Ingredients include yucca, plantains, potatoes, carrots, corn, onion, garlic, cilantro, and — of course — a large hunk of beef.

To be honest, I’m often underwhelmed by olla de carne. The meat is generally tough, and the flavor is rarely interesting. But I promise to keep searching for the perfect olla. It must be out there somewhere.

Sopa Negra

This black bean soup is hardly fancy, but on a cool afternoons in the cloudforest sopa negra hits the spot. Black beans form the base of the broth. Hard-boiled eggs provide a bit of heartiness. Sopa negra is then spiced up with onion, garlic and cilantro.

Sopa de Pejibaye

This is hands down my favorite Costa Rican soup. Sadly, few restaurants offer sopa de pejibaye on the menu. If you see it, order it.

Made from the delicious pejibaye fruit (see below), sopa de pejibaye is a bit like squash soup, but richer, creamier, and more flavorful.

The Specialties

Chifrijo

Over the past three decades, chifrijo has taken Costa Rica by storm. The name is a combination of chicharrón and frijoles (“beans”) – its two main ingredients. Chifrijo also includes rice, pico de gallo (tomato, onion, cilantro), and add-ons such as avocado or jalapeños.

The story of chifrijo began in Tibás, a working class suburb of San José. It was there that Miguel Cordero, owner of Cordero’s I bar, claims to have invented the tasty appetizer in the 1990s. After chifrijo started popping up in other restaurants, Cordero filed a patent for his creation.

In 2014 Cordero announced plans to sue 49 restaurants for $15 million for the unauthorized sale of chifrijo. Defendents included The Four Seasons and Hooters. In response, restaurants began offering the same dish under the name Chichifrijo, Chifrijol, El Innombrable (“The Nameless”) and, simply, Chicharrón & Frijoles.

Pejibaye

This starchy, fibrous fruit has been cultivated by indigenous groups for centuries. About the size of a small peach, pejibaye grows on tall palms in enormous bunches.

Raw pejibaye is hard and slightly toxic due to calcium oxalate crystals. When cooked with salt, however, the crystals disappear and pejibaye becomes soft, nutritious and delicious. The mild, slightly sweet flavor falls somewhere between a chestnut and a sweet potato.

When Spanish explorers arrived in Costa Rica, they found 30,000 trees under cultivation on the Atlantic coast. Today Costa Rica is the largest pejibaye exporter in the world, with roughly 5,000 acres under cultivation.

During peak harvest, street vendors sell cooked pejibaye around San José. Costa Ricans eat peeled pejibayes with a dab of mayonnaise, or cook them into a delicious soup.

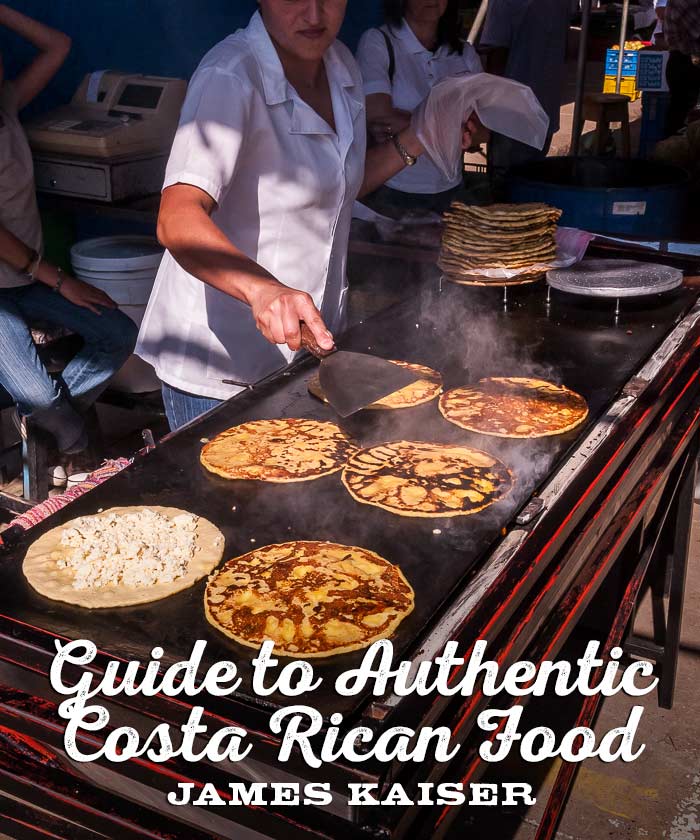

Chorreada

These sweet corn pancakes are a delicious alternative to gallo pinto for breakfast. The name comes from the Spanish verb chorrear (“to pour”). Chorreadas are mix of corn kernals, flour, milk, eggs and sugar. They are often served with a side of natilla (sour cream) and shredded cheese.

Gallos

These simple snacks are basically Costa Rican tacos. They consist of a heated corn tortilla, served with a dollop of beef, chicken or arracache, a popular starchy vegetable.

Gallos, which literally tanslates as “roosters,” are one of Costa Rica’s most popular bocas (“appetizers”). They are also further proof that Ticos love to name food after roosters.

Costa Rican Caribbean Food

Rondón

This coconut milk soup is the Caribbean Coast’s most famous dish. A hearty medley of fresh fish, crab, yucca, plantain, yam, vegetables and Caribbean spices.

Rondón is, in my opinion, the single best dish in Costa Rica. The very best rondón (which I reveal where to order in Costa Rica: The Complete Guide) can compete with the best dishes anywhere in Latin America.

Yes, it’s that good.

The name rondón derives from the English “run down.” As in, Caribbean cooks originally made rondón with whatever they could “run down.”

Rice & Beans

This is the most common dish on the Caribbean Coast. But unlike rice and beans served in the rest of Costa Rica, Caribbean rice and beans are slow-cooked with fresh coconut milk. The resulting flavor is sweet, savory and tropical.

Rice and beans are made with either black beans or red beans, depending on the cook. Order it with fresh fried fish and patacones — preferably overlooking the turquoise Caribbean — and you’ll never want to go back home.

Patty

Also spelled pattí, this baked empanada is filled with spicy ground meat. A spicy kick is delivered via habanero chiles, locally known as chile panameño (Panamanian chiles).

Locals sell patty in Puerto Viejo and Cahuita. You can also buy them from roadside vendors as you drive towards Limón.

Desserts

Tres Leches

Popular throughout much of Latin America, tres leches is by no means a Costa Rican specialty. But it’s often the tastiest dessert on the menu.

Tres leches consists of moist sponge cake soaked in tres leches (“three milks”). Those three milks are whole milk, evaporated milk, and sweetened condensed milk.

Pan Bon

This sweet, dark bread is a Caribbean specialty. It’s made with flour, unrefined sugarcane, butter, mild white cheese, cinnamon, nutmeg, vanilla, raisins and candied fruits.

The sweetness of pan bon falls somewhere between regular bread and cake, making it more of a light snack than a true dessert.